Chimpanzees and Chimpanzee Research in Uganda

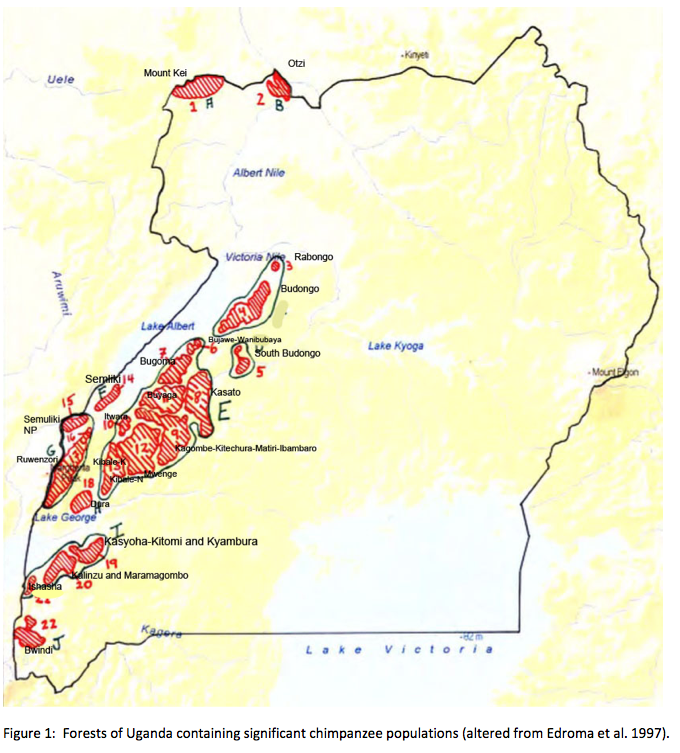

There may be 150,000 chimpanzees remaining in Africa, and of those, it is estimated that 4,000-5,700 survive in Uganda (Plumptre et al. 2003). Chimpanzees are classified as an endangered species by the IUCN. They are threatened by habitat loss everywhere they survive, and they are at risk from hunting in much of their range.

There are 22 chimpanzee populations in Uganda (Edroma et al. 1997), mostly clustered along the western border of the country. The site of Otzi is the easternmost extent of the species. Of the approximatley 5,000 chimpanzees in Uganda, perhaps 3% of that number, or 150 individuals, are to be found in the Semliki Mugiri community. The Nyabaroga and Muzizi communities contribute perhaps a hundred further individuals.

Chimpanzees of Uganda are fortunate in a number of ways, making their prospect for persisting a good one, compared to other populations across Africa. First, Ugandans tend to respect conservation area boundaries; for example, the Itwara Forest Reserve sits at the top of the escarpment, just 100s of meters from Toro-Semliki. It was neither guarded nor patroled during the chaotic Amin years, yet satellite images prove it is largely intact. Plumptre and colleagues (2003) maintain that Itwara is typical; protected areas in Uganda lose only a ‘tiny fraction’ of their forest to encroachment. Second, Ugandans have no tradition of eating chimpanzees as meat. This is not true elsewhere in Africa; many cultures view monkeys and apes as just another of many forest animals, and some people view ape meat as a delicacy; e.g., Nigerian and Congolese restaurants in Belgium (chimp on menu) serve chimpanzee meat. Not Ugandans; they consider chimpanzees too human-like to eat. Third, the stability of the government in the last 20 years has meant that scientists who work in the country have been able to sustain their research programs largely uninterrupted. This is good for conservation; where research sites are founded, the chimpanzees thrive.

HIstory

Vernon and Frances Reynolds initiated the first scientific study of chimpanzees in 1962 (Reynolds and Reynolds 1965) only two years after Jane Goodall began her research at Gombe. Despite this, Ugandan chimpanzee research had a slow start. Jane Goodall's spectacular success at Gombe, the popularity of the National Geographic films documenting her work, and Goodall's collaborative nature resulted in an explosion of science comign out of Gombe. The second most influential flurry of publications came out Tanzania's other site, Mahale, where Toshisada Nishida had established a site in 1965. Consequently, for many years Gombe was virtually synonymous with chimpanzee research in Africa.

In the late eighties and nineties, however, the advantages Uganda offered for research and the greater population numbers in Uganda led to an florescence of research there, and half a dozen research sites were established. The second Ugandan research site to be established was at the Kibale National Park, and it has become a beehive of activity beginning with early work by Ghiglieri in the 70s (Ghiglieri 1984) at Ngogo. In the early 80s Gilbert Isabirye-Basuta began studying a second community at Kibale, the Kanyawara community. He was soon joined by Richard Wrangham, who has directed a team there since (Wrangham et al., 1986). In the nineties Lwanga, Mitani and Watts revived work on the Ngogo community (Watts 1998, Mitani and Watts 1999, Lwanga 1996) and it now rivals Gombe, Mahale, Kanyawara and Tai (in west Africa) in research productivity.

I find only 16 articles published on Uganda chimpanzees 1985 or earlier—25 years after Goodall started at Gombe—but an astounding 423 since (a complete list of Uganda chimpanzees publications can be found here). There are seven active chimpanzee conservation or research initiatives in Uganda, and that doesn’t include the now-inactive site of Ishasha (Sept 1992, Shoeninger et al. 1999):

- Budongo (Reynolds and Reynolds 1965, Plumptre and Reynolds 1992)

- Bwindi/Impenetrable Forest (Stanford and Nkurunungi 2003)

- Kalinzu (Hashimoto 1995, Furuichi et al. 2001)

- Kibale-Kanyawara (Isabiry-Basuta 1988, Wrangham et al. 1992)

- Kibale-Ngogo (Watts 1998, Mitani and Watts 1999, Lwanga 1996)

- Kyambura (Poppenwimer 2000)

- Semliki (Hunt and McGrew 2002)

Cited Works

Edroma, E. L., N. Rosen and P.S. Miller (1997)Conserving the Chimpanzees of Uganda: Population and Habitat Viability Assessment for Pan troglodytes schweinfurthii. IUCN/SSC Conservation Breeding Specialist Group: Apple Valley, MN.

Furuichi, T., C. et al. (2001). Fruit availability and habitat use by chimpanzees in the Kalinzu Forest, Uganda: Examination of fallback foods. International Journal of Primatology 22(6): 929-945.

Furuichi, T., Hashimoto, C. and Tashiro, Y. 2001. Seasonal changes in habitat use by chimpanzees in the Kalinzu Forest, Uganda: extended application of marked nest census method. International Journal of Primatology 22, 913-928

Hashimoto, C. (1995). Population Census of the Chimpanzees in the Kalinzu Forest, Uganda: Comparison between Methods with Nest Counts. Primates 36(4): 477-488.

Hashimoto, C. 1995. Population census of the chimpanzees in the Kalinzu Forest, Uganda: comparison between methods with nest counts. Primates, 36, 477-488.

Hunt, K. D. and W. C. McGrew (2002). Chimpanzees in the dry habitats of Assirik, Senegal and Semliki Wildlife Reserve, Uganda. In: Behavioural Diversity in Chimpanzees and Bonobos, C. Boesch, G. Hohmann and L.F. Marchant (eds.) Cambridge University Press, pp. 35-51.

Isabiry-Basuta, G. (1988). Food Competition among Individuals in a Free-Ranging Chimpanzee Community in Kibale Forest, Uganda. Behaviour 105: 135-147.

Lwanga, J. S. (2006). "Spatial distribution of primates in a mosaic of colonizing and old growth forest at Ngogo, Kibale National Park, Uganda." Primates 47(3): 230-238.

Mitani, J. C. and D. P. Watts (1999). Demographic influences on the hunting behavior of chimpanzees. American Journal of Physical Anthropology 109(4): 439-454.

Mitani, J.C., Struhsaker, T.T. and Lwanga, J.S. 2000. Primate community dynamics in old growth forest over 23.5 years at Ngogo, Kibale national park, Uganda: implications for conservation and census methods. International Journal of Primatology 21, 269-286.

Newton-Fisher, N.E. 1999. The diet of chimpanzees in the Budongo Forest Reserve, Uganda. African Journal of Ecology 37, 344-354.

Newton-Fisher, N.E., Reynolds, V. & Plumptre, A.J. 2000. Food supply and chimpanzee (Pan troglodytes schweinfurthii) party size in the Budongo Forest Reserve, Uganda. International Journal of Primatology 21, 613-628.

Plumptre, A. & Reynolds, V. 1996. Censusing chimpanzees in the Budongo forest. International Journal of Primatology 17, 85-99

Plumptre, A.J. & Grieser-Johns, A.D. 2001. Changes in Primate Communities following Logging Disturbance. pp. 71-92 In: The cutting edge: conserving Wildlife in logged Tropical Forests. Eds: R.A. Fimbel, A. Grajal, and J.G. Robinson. Columbia University Press, New York.

Plumptre, A.J. & Reynolds, V. 1997. Nesting behaviour of chimpanzees: implications for censuses. International Journal of Primatology 18, 475-485.

Plumptre, A.J.; Cox, D.; Mugume, S. (2003) The Status of Chimpanzees in Uganda. Albertine Rift Technical Reports Series Volume: 2, pages: 1-76.

Poppenwimer, C. J. (2000). Encounter in Uganda between chimpanzees Pan troglodytes and a leopard Panthera pardus. African Primates 4(1-2): 75-76.

Reynolds, v. (1997) History of Chimpanzee Studies in Uganda. In: Conserving the Chimpanzees of Uganda: Population and Habitat Viability Assessment for Pan troglodytes schweinfurthii, (E.L. Edroma, N. Rosen and P.S. Miller (eds.). IUCN/SSC Conservation Breeding Specialist Group: Apple Valley, MN, p. 25-30.

Reynolds, V. 1992. Chimpanzees in the Budongo Forest 1962-1992.Journal of Zoology 228, 695-699.

Reynolds, V., and Reynolds, F. 1965. Chimpanzees of Budongo Forest. In Devore, I. (ed.) Primate behaviour, Holt, Rinehart-Winston, New York.

Schoeninger, M. J., J. Moore, and J.M Sept. (1999). Subsistence strategies of two "savanna" chimpanzee populations: The stable isotope evidence. American Journal of Primatology 49(4): 297-314.

Sept, J. M. (1992). Was there no place like home? A new perspective on early hominid archaeological sites from mapping of chimpanzee nests. Current Anthropology 33(2): 187-207.

Stanford, C. B. and J. B. Nkurunungi (2003). Behavioral ecology of sympatric chimpanzees and gorillas in Bwindi Impenetrable National Park, Uganda: Diet. International Journal of Primatology 24(4): 901-918.

Watts, D. P. (1998). Coalitionary mate guarding by male chimpanzees at Ngogo, Kibale National Park, Uganda. Behavioral Ecology and Sociobiology 44(1): 43-55.

Wrangham, R. W. et al. (1992). Female social relationships and social organization of Kibale Forest chimpanzees.

Wrangham, R.W., Chapman, C.A., Clark-Arcadi, A.P., and Isabirye-Basuta, G. 1986. Social ecology of Kanyawara chimpanzees: implications for understanding the costs of great ape groups. In: Great Ape Societies. Eds: W.C. McGrew, L.F. Marchant and T. Nishida. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.