History of the Reserve

The Toro-Semliki Wildlife Reserve entered European consciousness on March 14, 1864, when a Samuel Baker expedition crested the rift escarpment bringing an immense body of water into view. Baker named it Lake Albert (Bishop, 1967). If any land was visible across the lake, it would have been a peninsula that juts northward into the lake, now the site of the fishing village of Ntoroko.

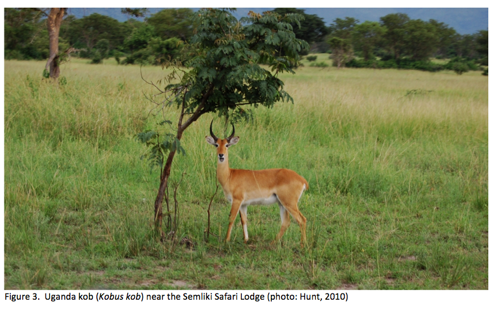

Scattered remains of pottery on exposed soil in the reserve suggests Toro-Semliki was rather densely populated in the distant past, at least in comparison to current and historic numbers. Whatever the size of the population in the distant past, it was dramatically depopulated between 1898 and 1915 when a sleeping sickness epidemic swept through the area (Bishop, 1967; Verner and Jenik, 1978). Those who survived the epidemic were evacuated by the Uganda Protectorate government (Verner and Jenik, 1978), leaving the area that is now the reserve nearly empty. Authorities seized on the opportunity provided by the exodus from the area to create a conservation area. Thus, the approximately 548 km2 ‘Toro Game Reserve’ was gazetted in 1929 by Uganda Protectorate General Notice 546. The high density of Uganda kob in the area was a crucial factor the reserve’s creation, and the reserve was conceived as a key habitat for conserving Uganda’s dwindling Uganda kob population (Lamprey and Michelmore, 1996).

Since being gazetted, the name of the reserve was changed frequently. The Toro Game Reserve was renamed the Semuliki Game Reserve, then the Toro Wildlife Reserve, then the Semliki Valley Wildlife Reserve, then the Semliki-Toro Wildlife Reserve, and finally to the Toro-Semliki Wildlife Reserve. The reserve is often confused with the Semuliki National Park, 10 km to the southwest, more so in the past when one was named Semliki National Park and the other Semliki Valley Wildlife Reserve. Renaming SNP ‘Semuliki’ was meant to help distinguish the two. The confusion is unfortunate because despite their proximity their habitats are strikingly different; TSWR is principally grassland, and SNP is predominantly rainforest.

In the 1950s with the introduction of the outboard motor the human population surrounding the reserve and northwards increased dramatically. Fishing villages expanded and proliferated all along the shores of Lake Albert (Bishop, 1967). With respect to the reserve, the most significant of the villages is Ntoroko, situated inside the reserve on a peninsula extending into the lake. The village was grandfathered into the reserve, intended as an outpost for locals to allow them to continue to fish in the lake. Notoroko has not remained a small outpost, but has grown steadily from a few hundred fishermen to a village of thousands, including many refugees from war-torn Congo (Bundibugyo District Report, 2002). By the early 2000s fish were being trucked out of the reserve by the ton, and local fisherman report that fish in the lake are smaller and less abundant than in the recent past.

In accord with the Protectorate's conception of the reserve's value, Uganda kob flourished in the reserve, numbering 20,000 by the late 60s (Kyeyune, 1969). The abundance of kob and other ungulates supported a diverse community of predators, including lions, leopards and hyena, which made the reserve an unexcelled venue for viewing wildlife up close. In the 50s and 60s the lodge was one of East Africa’s most popular safari destinations, and the 40 rooms of the lodge were said to run at an 80% occupancy rate. The drive across the grassland approaching the lodge was made amidst vast herds of kob, and once at the lodge visitors recall watching from the comfort of the lodge veranda as lions stalked and killed kob. Hiking to the lodge was an audacious adventure for the few intrepid locals who could muster up the courage. Hikers descended the steep escarpment from the north and east and walked across the savanna to the lodge at the center of the reserve.

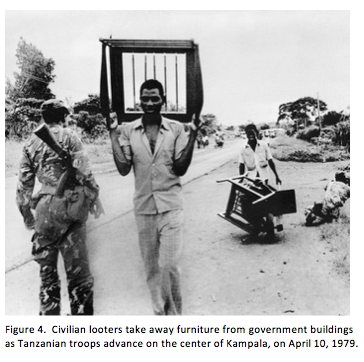

As popular as Semliki was in the 60s, the 70s brought the Idi Amin years, and Uganda became a much less welcoming destination; visitors to the lodge dwindled to a trickle. As the Ugandan economy struggled, Amin found himself unable to feed his army, an inconvenience he solved by allowing the military to poach wildlife in conservation areas (Avirgan and Honey 1983). Amin’s inexplicable military incursion into Tanzania, thus provoking the 1978/79 Uganda-Tanzania war, had disastrous consequences for Semliki. In the war zone, the reserve was neglected, and as the war wound down in revenge the victorious Tanzanians slaughtered wildlife throughout southwestern Uganda from Queen Elizabeth as far north as Semliki. Locals describe the Tanzanian army hauling truckloads of Uganda kob from Semliki, transported south to be sold in Tanzanian markets. After the war, poaching in the reserve continued at a high rate, and the already diminished kob population fell to a tenth of its previous numbers (Verner and Jenik, 1978). Poacher fires and snares dotted the reserve, and large, organized poaching bands crossed over the river from the Congo, using dogs and sometimes even automatic weapons to poach from the reserve (Lamprey and Michelmore, 1996; Stubblefield, 1993). Local farmers grazed their cattle on reserve land with impunity (Lamprey and Michelmore, 1996; Stubblefield, 1993) and kob were seen as unwelcome competitors for graze. Lions and leopards were viewed as a threat to cattle, and poisoned.

Locals remember a ruined lodge, the furniture and fittings having been sold off by the staff, the formerly bustling lodge grounds still, the lodge without occupants, abandoned except for the solitary manager. The lodge was burned to the ground in the mid-eighties, some say to destroy evidence that the staff had stripped it bare. In the 80s and early 90s, the sporadic presence of game guards in the reserve did little to preserve wildlife, since guards were paid only sporadically, had little in the way of equipment, and were vastly outnumbered by poachers. The reserve was for all intents and purposes left to poachers and encroachers.

The reserve was further compromised by local politics and its consequent population movement. When the Rwenzori National Park was established just to the south of the reserve in 1991, locals were expelled and many shifted to the only unsettled land nearby, a wedge of land in the southern part of the reserve known as Kyabandara. Authorities were now faced with a stituation where reserve’s raison d’etre, the kob, were nearly extinct, cattle grazed on nearly the entire western half of the reserve, poachers were a constant presence throughout the reserve, in the north Ntoroko clamored for more space for their exploding population, major predators were locally extinct, to the south Kyabandara was dotted with farms, and to the west the local village, Karagutu, was experiencing the beginning of what has since become a massive influx of Congolese refugees. There was frequent discussion of abandoning the reserve completely, de-gazetting it, and focusing on other conservation areas that held more promise.

In the early 90s, Uganda National Parks (now the Uganda Wildlife Authority) assessed the situation and made a commitment to save the reserve. In an effort to leverage private resources to bolster their limited capital, Uganda authorities invited private companies to bid on a concession in the reserve that would allow private investors to build a new lodge. The Uganda Safari Company won the bidding in 1994, and by 1996 they were operating a modest tented camp; in 1998 they opened the newly constructed Semliki Safari Lodge, several hundred meters to the west of the old lodge. The old lodge foundation still remains, and has been built up into staff housing.

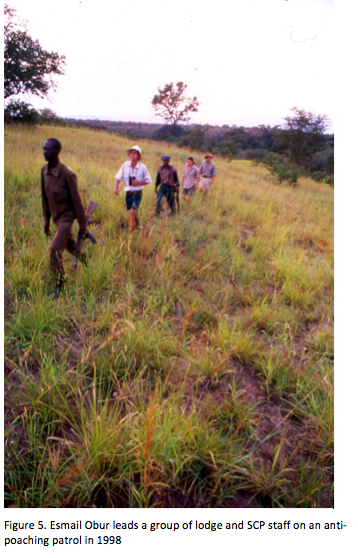

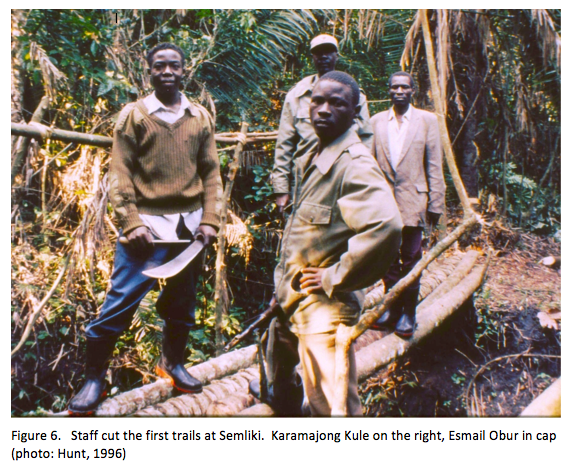

Beginning in 1996, Semliki Safari Lodge management provided transport and other logistical support that allowed increased anti-poaching patrols, vastly improving the effectiveness of UWA law enforcement efforts. With ramped up anti-poaching activities and the presence of the new lodge and its staff, poaching declined and wildlife began a gradual recovery. Many remember Game Guard Esmail Obur’s courageous and relentless—some might even say ruthless—pursuit of poachers in the mid- and late-90s.

Among the diverse wildlife in the reserve are chimpanzees, an unusual population because chimpanzee typically prefer more forested habitats. In 1995 Prof. Kevin Hunt of Indiana University became aware of the reserve as he was searching for a dry-habitat chimpanzee population to serve as a model for the behavior and ecology of early human ancestors. In July 1996 he arrived at the reserve to survey the chimpanzee population and with support of the Semliki Safari Lodge staff and owners and UWA ranger Esmail Obur, he established that the reserve sustained three, possibly even four chimpanzee communities. One was on the northern boundary of the reserve, along the Muzizi River. Unfortunately, the Muzizi forest was heavily logged in the early 2000s, and it seems likely that few if any chimpanzees survive there. A second population is located in forests supported by the Mugiri River and its tributaries, which flow down escarpment to the Mugiri on the reserve floor. This became the study population. A third population of chimpanzees is found in the southwest border of the reserve, in the Nyabaroga Valley. Unfortunately, because the Nyabaroga valley marked the boundary of the reserve, this community was half in and half out of the reserve. As the reserve was being resurrected in the mid-90s, the Uganda Wildlife Authority Boundaries Committee was established to survey conservation areas. When Semliki was being surveyed, Prof. Hunt argued that the Nyabaroga valley, just outside the reserve and populated by only a few families, should be added to the reserve. On September 3, 1997, UWA Boundaries Committee representative Richard Lamprey and Prof. Hunt walked a proposed border with representatives of the local government, which was open to ceding Nyabaroga to the reserve, providing certain conditions were met. In essence, the degraded and heavily populated Kyabandara area in the south, the area where displaced people from the Rwenzori National Park had settled, was traded for the Nyabaroga valley, which is now part of the reserve. A possible fourth community of chimpanzees are found along the Wasa River (see Fig. 1), but it now seems most likely that these chimpanzees are part of a dispersed and very large community that spends most of its time near the Mugiri.

In 1996 SCP began the construction of what eventually became 50 km of trails. As the trails crept up the escarpment along the eastern edge of the reserve, poaching camps and snares were discovered. The presence of researchers on the escarpment discouraged poachers, and the trails allowed UWA rangers to patrol more effectively. Poaching activity across the eastern boundary of the reserve decreased.

Despite these promising developments, political instability in western Uganda plagued the reserve in the mid-90s, slowing the recovery of wildlife and hampering conservation initiatives. On June 16, 1997 a rebel group calling itself the Allied Democratic Front (ADF) engaged the Ugandan army (UPDF) in a bloody battle just outside the southern boundary of the reserve. Scores were killed. For five years the ADF roamed the area between the northern part of the reserve and the southern Rwenzoris, and east and west from the Congo border to Fort Portal. They mounted sporadic assaults on local people, often striking small villages unexpectedly, killing a few unlucky local people, and retreating into the bush. For example, the BBC reported 21 slaughtered on Dec. 6, 1997; another 13 were reported killed on April 12, 1998; eight more were murdered on May 1, 1998. Perhaps the ADFs cruelest attack came on June 9, 1998, when ADF locked more than 40 Kichwamba Technical School students in their dormitory and burned it to the ground, killing all the students. In December 1999, ADF attacked the Katojo prison in Fort Portal and freed 365 prisoners, many of them ADF. Ugandan authorities responded by installing a large UPDF contingent in the reserve, and for years, from 1998 to 2002, soldiers accompanied researchers and tourists whenever they entered the forest.

The most severe blow to SCP and local conservation came in llate 1999 when the ADF installed themselves in the chimpanzee study area, attracted by the remoteness of the site and the strategic value of the research trails. There followed an extensive military action early in 2000 meant to kill or displace the ADF. During a skirmish on February 4, 2000 three UPDF troops guarding the lodge were killed by a rocket propelled grenade, and the lodge and research staff were evacuated. Twenty five civilians were killed in Bundibugyo on January 15, 2000. On May 29, UPDF forces shelled 50 ADF hiding in the Muzizi forest (New Vision report, May 30, 2000). There were major battles May 12-15, 2001 and August 20, 2001. Finally, in November 2001, UPDF forces fired tens of mortars onto the escarpment in the largest and final UPDF-ADF battle on the escarpment. Many ADF were killed, and the survivors were finally pushed out of the reserve. Although remnants of the ADF may still exist in the Congo, they were expelled from the reserve by early 2002. SCP continued its activities during all but the most severe ADF incursions and UPDF battles and the lodge continued to operate. Poaching patrols remained in place for most of the military activity, and the reserve continued to recover.

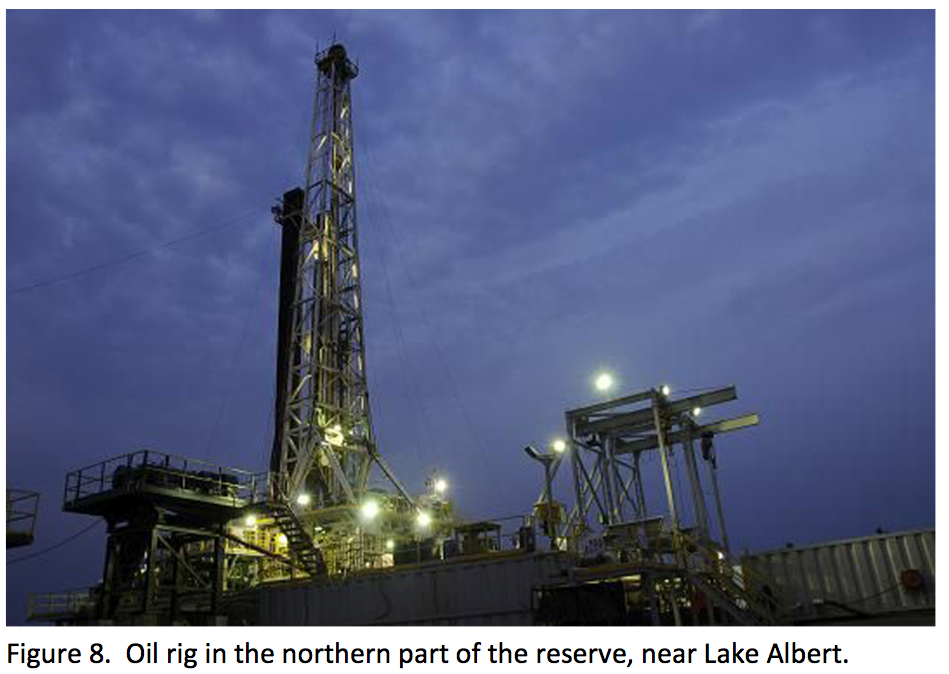

Many believe that the government's principal motivation in securing political stability in the reserve was the discovery of large oil reserves in the rift valley. The presence of oil reserves in Western Great Rift was known as far back as before WW II when the Shell Oil Company explored the reserve in 1938. Interest in the possibility of oil in the reserve has waxed and waned in the iterim (Johnson, 2003). In the 80s and 90s, the government conducted surveys, and in 1997 the Heritage Oil Company acquired an exclusive oil exploration concession around the reserve. One upshot was that the Ugandan government and Heritage worked together to improve roads into the reserve. In 1996, when the rehabilitation of the reserve began, the main road from Fort Portal was a precarious and dangerous 20-foot-wide dirt track hugging the mountainside, prone to collapses and landslides. It is now a broad and stable gravel highway, easy to traverse, and much safer.

In 1998 Heritage began seismic surveys in the reserve (Johnson, 2003; pers. obs.), and soon after a large encampment was established near the lake. Early in 2002 a major widening and improvement of the road into the reserve allowed Heritage to deliver a drilling rig to the lake, and drilling began on September 27, 2002. Although the drilling was not near the chimpanzee range, Heritage cooperated with SCP in primate conservation initiatives, and ultimately provided important financial support for the project in 2004. Heritage was soon joined in their venture by the larger Tullow Oil Company, and in 2010 Heritage sold their interests in the reserve and environs to Tullow, which in turn sold most of its stake to two even large oil companies, TOTAL and the Chinese oil company CNOOC. Oil reserves are believed to be huge, so huge that there is talk of constructing a pipeline from Lake Albert to the Indian Ocean port town of Mombasa, Kenya. To date the vast majority of the habitat disturbance related to seismic surveys and drilling has been in the grasslands on the rift floor. Plans to build oil-refining capacity near or even within the reserve are reported. Environmental impacts could be significant, though both the government and oild companies have vowed to keep impacts low.

In 1998 Heritage began seismic surveys in the reserve (Johnson, 2003; pers. obs.), and soon after a large encampment was established near the lake. Early in 2002 a major widening and improvement of the road into the reserve allowed Heritage to deliver a drilling rig to the lake, and drilling began on September 27, 2002. Although the drilling was not near the chimpanzee range, Heritage cooperated with SCP in primate conservation initiatives, and ultimately provided important financial support for the project in 2004. Heritage was soon joined in their venture by the larger Tullow Oil Company, and in 2010 Heritage sold their interests in the reserve and environs to Tullow, which in turn sold most of its stake to two even large oil companies, TOTAL and the Chinese oil company CNOOC. Oil reserves are believed to be huge, so huge that there is talk of constructing a pipeline from Lake Albert to the Indian Ocean port town of Mombasa, Kenya. To date the vast majority of the habitat disturbance related to seismic surveys and drilling has been in the grasslands on the rift floor. Plans to build oil-refining capacity near or even within the reserve are reported. Environmental impacts could be significant, though both the government and oild companies have vowed to keep impacts low.

While the Toro-Semliki Wildlife Reserve faces challenges—chronic shortages of staff, funding challenges, limited law enforcement, poaching, encroachment, oil exploration—the future of the reserve seems bright. Toro-Semliki has rebounded dramatically from neglect in the 80s, and a look through photos here on this website shows that it is once again the spectacular natural wonder visitors knew in the 50s and 60s. In partnership with the Uganda Wildlife Authority and the Semliki Safari Lodge, the Semliki Chimpanzee Project is committed to assuring the continued existence of chimpanzees and other wildlife in the reserve, and the future of the reserve itself.