Project History

1. Origins: 1990-1995

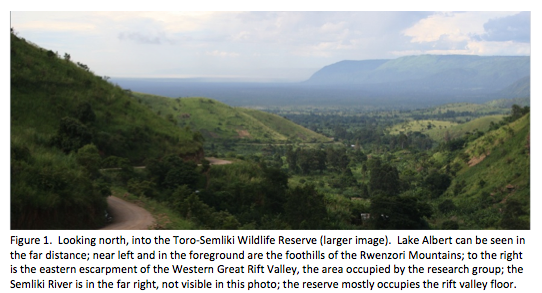

The seeds of w hat became the Semliki Chimpanzee Project extend back to 1990, when project founder and director Kevin Hunt was a Postdoctoral Fellow, working in the Kibale forest, southern Uganda. Prof. Hunt participated with a number of chimpanzee researchers in what amounted to an informal survey of Uganda's chimpanzes and the trip included a drive to the edge of the rift escarpment where he and his colleagues looked down into the reserve, a view almost exactly the same as the image in Figure 1. In contrast the the view to the left, rising from the rift valley floor into the mid-morning air were perhaps 10 columns of smoke, poacher camps. An UWA official described the reserve as lawless and empty, populated only by roving bands of poachers and bandits.

hat became the Semliki Chimpanzee Project extend back to 1990, when project founder and director Kevin Hunt was a Postdoctoral Fellow, working in the Kibale forest, southern Uganda. Prof. Hunt participated with a number of chimpanzee researchers in what amounted to an informal survey of Uganda's chimpanzes and the trip included a drive to the edge of the rift escarpment where he and his colleagues looked down into the reserve, a view almost exactly the same as the image in Figure 1. In contrast the the view to the left, rising from the rift valley floor into the mid-morning air were perhaps 10 columns of smoke, poacher camps. An UWA official described the reserve as lawless and empty, populated only by roving bands of poachers and bandits.

At that time Prof. Hunt was drafting an article on bipedalism in Tanzanian chimpanzees, an article that was to appear in 1994. Hunt found that chimpanzees were bipedal most often when they were feeding on fruits that were found only in the very driest part of their habitat, a habitat that was mostly forest. He reasoned that chimpanzees that were entirely restricted to such dry, open habitats might be much more bipedal than normal chimpanzees, and perhaps human-like in other ways, tool.

In 1993 Hunt began searching for a dry-habitat site where he could test this hypothesis. After unsuccessful inquiries into sites in Mali and Senegal, he heard rumors of plans to rehabilitate Semliki. In 1995 he was put in touch with a business now known as the Uganda Safari Company (then called the Green Wilderness Group) that had submitted a bid to build and manage a new lodge in the reserve. Company founder Jonathan Wright invited Hunt to visit Semliki to see if a research project might be possible there.

2. Beginnings: 1996

In July, 1996 study of the Mugiri chimpanzee community began when Prof. Hunt arrived for a three-month stint in the reserve. There was no lodge at that time, but the Uganda Safari Co. had established a primitive tented tourist camp, where they generously offered lodging for Prof. Hunt. UWA, now committed to reviving the reserve, established an outpost where several rangers were stationed, one of whom was assigned to track chimpanzees with Hunt. Few tourists visited the reserve back then, leaving the safari company staff free to accompany Hunt and the rangers as they tracked chimpanzees.

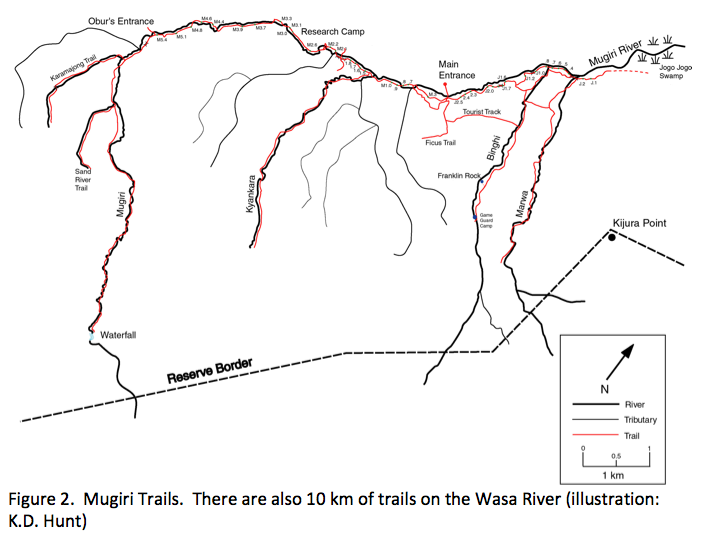

Before Hunt arrived tourist camp, staff had heard and occasionally seen chimpanzees in the Wasa River gallery forest, near the ruins of the old lodge. However, in the first few days of Hunt’s visit it became clear that the chimpanzees could be discovered more reliably at the Mugiri River, a 5 km drive across the savanna (see area map). The Uganda Safari Company provided transport, and SCP, consisting of Hunt and a ranger, began daily searches in the Mugiri forest. The project’s first chimpanzee was spotted on July 12, near what is now known as trail marker M2.1, just north of the current research camp. Within days Hunt was making observations of over 45 minutes.

Before Hunt arrived tourist camp, staff had heard and occasionally seen chimpanzees in the Wasa River gallery forest, near the ruins of the old lodge. However, in the first few days of Hunt’s visit it became clear that the chimpanzees could be discovered more reliably at the Mugiri River, a 5 km drive across the savanna (see area map). The Uganda Safari Company provided transport, and SCP, consisting of Hunt and a ranger, began daily searches in the Mugiri forest. The project’s first chimpanzee was spotted on July 12, near what is now known as trail marker M2.1, just north of the current research camp. Within days Hunt was making observations of over 45 minutes.

In early August, 1996 Hunt hired two porters (often called slashers), Ali “Karamajong” Kule and Eriik Katsutama to begin cutting trails. They were to work for the project for over a decade. Game Guard Esmail Obur was drafted into the project part-time, and trail construction began in earnest. As the trails crept up the escarpment along the eastern edge of the reserve, poaching camps and snares were discovered. One small—probably 2-person—illegal logging camp was discovered, a ‘pit-sawyering’ operation. The snares were removed and the camps destroyed. The presence of slashers and researchers on the escarpment discouraged poachers, and the trails allowed UWA rangers to patrol more effectively. Poaching activity across the eastern boundary of the reserve decreased.

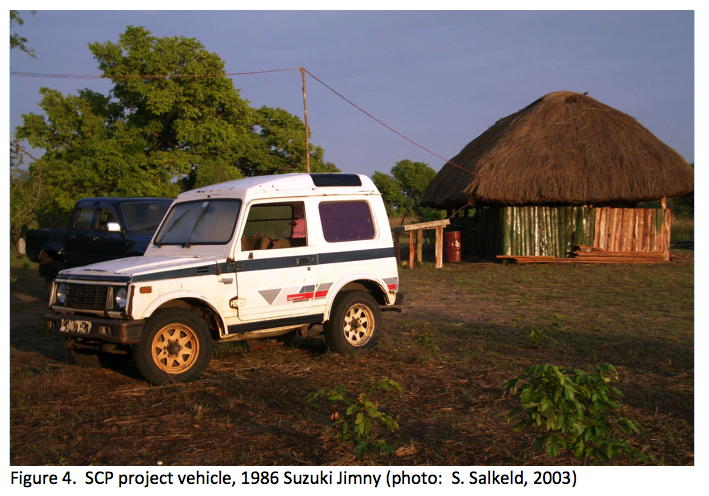

In September, 1996 Hunt made the project’s first major purchase, a Suzuki Jimny (marketed at the “Samarai” in the US). While some of his assistants still remember the Suzuki with affection, the vehicle fell apart faster and in more different ways than any automobile Prof. Hunt has ever known. Miraculously, though out of active service for some years, it still runs occasionally today, 15 years later, and we use it now and then to haul water or thatch.  During this first stint Prof. Hunt observed chimpanzees an average of an hour and a half a month. He found it encouraging that some individuals—always females it seemed—were more curious than wary when people approached. Once, high on the escarpment, a female approached Hunt and a ranger and stared for over a minute, looking away as if to leave, then looking back again as if she couldn’t believe her eyes, and finally leaving slowly.

During this first stint Prof. Hunt observed chimpanzees an average of an hour and a half a month. He found it encouraging that some individuals—always females it seemed—were more curious than wary when people approached. Once, high on the escarpment, a female approached Hunt and a ranger and stared for over a minute, looking away as if to leave, then looking back again as if she couldn’t believe her eyes, and finally leaving slowly.

In his initial three months at the reserve, Prof. Hunt systematically surveyed the reserve for chimpanzees. Because chimpanzee sleeping platforms persist for weeks and even months, establishing the range of chimpanzees is relatively easy. He found nests and heard the pant-hoots (chimpanzee vocalizations) in the Muzizi River (map), even though the forest there had been thinned, presumably by illegal logging. This forest continued to suffer illegal logging, mostly, we believe, to feed the charcoal making industry in the area, largely to supply the fishing village of Ntoroko.

A further population was found in forests flanking the Nyabaroga Valley, where both nests and pant-hoots were heard. Unfortunately, because the Nyabaroga valley marked the boundary of the reserve, this community was half in and half out of the reserve. Here SCP (and the chimpanzees) were lucky. The same time the reserve was being resurrected in the mid-90s, the Uganda Wildlife Authority Boundaries Committee had been established to survey conservation areas. When Semliki was being surveyed, Prof. Hunt argued to the Boundaries Committee that the Nyabaroga valley, just outside the reserve and very nearly unpopulated, should be added to the reserve. On September 3, 1997, UWA Boundaries Committee representative Richard Lamprey and Prof. Hunt walked a proposed border with representatives of the local government, which was open to ceding Nyabaroga to the reserve, if certain conditions were met. In essence, the degraded and heavily populated Kyabandara area in the south, an area inside the reserve where displaced people from the Rwenzori National Park had settled, was traded for the Nyabaroga valley, which is now part of the reserve.

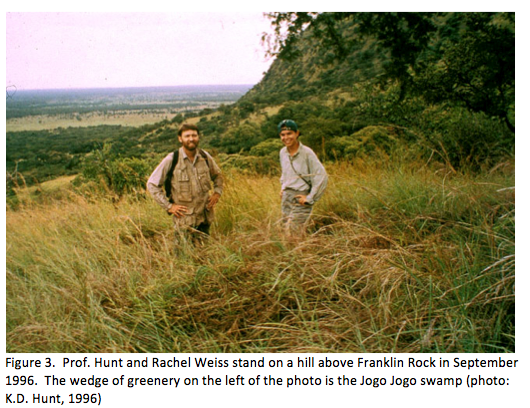

Prof. Hunt hired SCP’s first Assistant Project Director in September, Rachel Weiss, who arrived just before Hunt’s departure. She was to stay eight months, a service invaluable to the project in its first year. SCP now faced the task of ‘habituating’ the chimpanzees, making them used to the presence of humans. Habituation can be quick, as it was for Jane Goodall at Gombe, or it can be long and painstaking process. A team attempted to habituate dry habitat chimpanzees in Mt. Assirik, Senegal, and gave up after a decade, but a team led by Jill Pruetz was successful relatively quickly at nearby Fongoli, Senegal. Unfortunately, Semliki is more like Mt. Assirik than Fongoli. Weiss pushed observation minutes up to nearly two hours a month, not as high as might be expected based on e.g. Goodall’s progress in the first eight months at Gombe, but encouraging nonetheless. APD biographies can be found here.

Prof. Hunt hired SCP’s first Assistant Project Director in September, Rachel Weiss, who arrived just before Hunt’s departure. She was to stay eight months, a service invaluable to the project in its first year. SCP now faced the task of ‘habituating’ the chimpanzees, making them used to the presence of humans. Habituation can be quick, as it was for Jane Goodall at Gombe, or it can be long and painstaking process. A team attempted to habituate dry habitat chimpanzees in Mt. Assirik, Senegal, and gave up after a decade, but a team led by Jill Pruetz was successful relatively quickly at nearby Fongoli, Senegal. Unfortunately, Semliki is more like Mt. Assirik than Fongoli. Weiss pushed observation minutes up to nearly two hours a month, not as high as might be expected based on e.g. Goodall’s progress in the first eight months at Gombe, but encouraging nonetheless. APD biographies can be found here.

On Prof. Hunt’s return to the US in October he drew on the strength of his initial observations to submit a National Science Foundation proposal to their small grants for exploratory research program. It was funded, and SCP was guaranteed a future for two more years.

3. Terrorist group slows progress: 1997-2002.

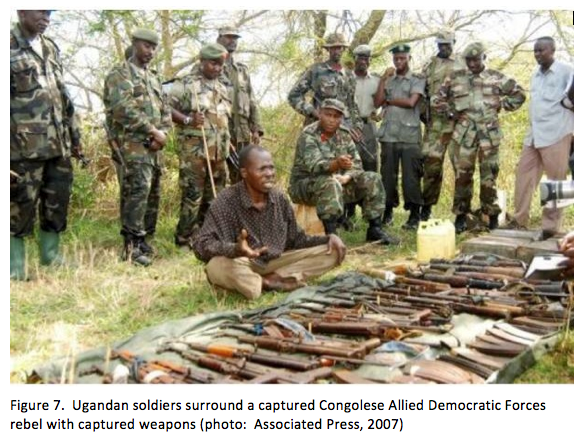

Rachel Weiss finished her stint in the reserve in May 1997 and was replaced by a well-meaning but not very capable philosophy doctoral student who, though eager, demonstrated that not everyone who wishes to study primates is cut out for research in the wilderness. In the first week he got lost going to the toilet, and game guards were frustrated that he seemed to have great difficulty in the forest. He was replaced by a student from Indiana University, but she had hardly settled in when on June 16 there came news of a deadly attack on the town of Bundibugyo, only 20 km from the reserve. A ragtag band of paramilitary bandits, calling themselves the Allied Democratic Forces (or sometimes, Allied Democratic Front) (ADF) attacked civilians, and were repulsed by the Ugandan Army (UPDF) only after scores were killed.  The ADF, despite their name, had no political agenda; they were essentially parasites, preying on the resources of local people, attacking remote villages to steal food, cash, and alcohol, then disappearing into the wilderness until their supplies ran out. Weakened by the UPDF but never entirely eliminated, the ADF were to remain a danger to local Ugandans and to those of us who worked in the reserve until 2002. Research was suspended following the attack, staff were evacuated, and the SCP Assistant Project Director returned to the US. Staff remained outside the reserve until Prof. Hunt arrived on July 10. When he arrived, local authorities assured SCP that the ADF were defeated, and there was no further danger. This was to be an often-repeated assessment over the next five years, through many subsequent attacks.

The ADF, despite their name, had no political agenda; they were essentially parasites, preying on the resources of local people, attacking remote villages to steal food, cash, and alcohol, then disappearing into the wilderness until their supplies ran out. Weakened by the UPDF but never entirely eliminated, the ADF were to remain a danger to local Ugandans and to those of us who worked in the reserve until 2002. Research was suspended following the attack, staff were evacuated, and the SCP Assistant Project Director returned to the US. Staff remained outside the reserve until Prof. Hunt arrived on July 10. When he arrived, local authorities assured SCP that the ADF were defeated, and there was no further danger. This was to be an often-repeated assessment over the next five years, through many subsequent attacks.

Prof. Hunt and staff returned to the reserve and—despite ADF attacks—had a productive month in the reserve, extending observations and re-starting the project; only two weeks after returning to the reserve, on July 28, 1997, Prof. Hunt followed a feeding party to their nesting site and ‘nested’ a chimpanzee, a first for Semliki.

In this same second visit to Semliki, Prof. Hunt discovered that chimpanzees at Semliki dig drinking “wells.” On August 12, 1997 he saw a female chimpanzee dig a hole in the sandy riverbank of the Mugiri River. She turned away, plucked a leaf from a nearby sapling, and the returned to the drinking hole to use the leaf to dip out water. The behavior was puzzling because the clear-flowing and placid Mugiri River, from which Prof. Hunt and his staff drink, was less than a meter from the hole. Semliki was the first place where chimpanzees were observed to dig these sorts of wells (Hunt, et al., 1999), and is one of only three places where it has been seen (Assirik and Fongoli are the others). The purpose of the wells unclear, since they are often dug in streamside sand, within centimeters of gently flowing streams from which the chimps could easily drink.

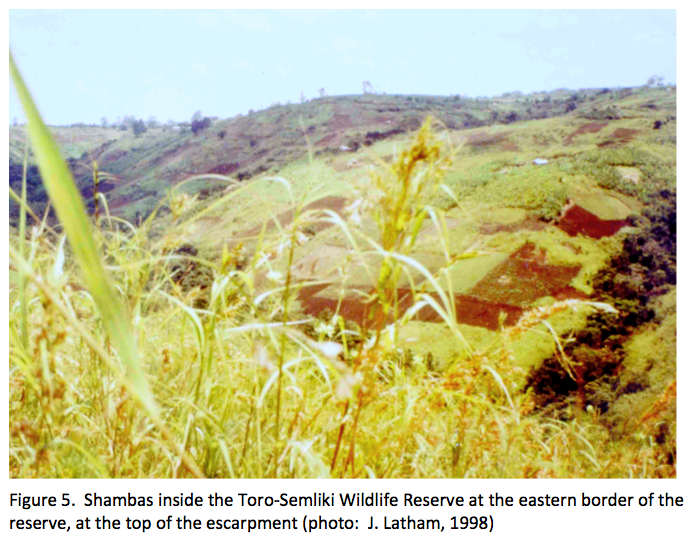

In September Jim Latham, a young graduate from UC Davis, arrived to take over as APD. He arrived just in time to overlap with Prof. Hunt, and remained through March 1998. Fortunately, the ADF were quiet during his tenure at Semliki, and he was able to focus on habituation. Latham was an energetic chimpanzee tracker, spending long hours in the forest searching, and so it was a surprise that observations improved little  during his tenure. When Prof. Hunt returned for a third visit in January of 1998, as Latham had found, the chimpanzees were difficult to locate and when discovered quickly disappeared. Something unusual was going on. In late 1997 and early 1998 SCP staff saw burning at the top of the escarpment, inside the reserve. Local farmers were staking out shambas (local gardens) in the reserve, inside the chimpanzee range. Soon corn and hastily thrown up structures could be seen creeping over the top of the escarpment, inside the reserve. This was a surprise. While SCP had discovered snares frequently when the trails were first being cut, the reserve boundaries seemed to be largely respected by local neighbors. The danger of this encroachment became apparent in March of 1998 when the reserve warden received news that a juvenile chimpanzee had been speared at the top of the escarpment as it raided a shamba. Confrontations with farmers might explain why it was the males at Semliki that were most leery of humans: males are known to raid shambas much more often than females. Such raiding might account for the fact that from the beginning of SCP females seemed more tolerant of humans than males.

during his tenure. When Prof. Hunt returned for a third visit in January of 1998, as Latham had found, the chimpanzees were difficult to locate and when discovered quickly disappeared. Something unusual was going on. In late 1997 and early 1998 SCP staff saw burning at the top of the escarpment, inside the reserve. Local farmers were staking out shambas (local gardens) in the reserve, inside the chimpanzee range. Soon corn and hastily thrown up structures could be seen creeping over the top of the escarpment, inside the reserve. This was a surprise. While SCP had discovered snares frequently when the trails were first being cut, the reserve boundaries seemed to be largely respected by local neighbors. The danger of this encroachment became apparent in March of 1998 when the reserve warden received news that a juvenile chimpanzee had been speared at the top of the escarpment as it raided a shamba. Confrontations with farmers might explain why it was the males at Semliki that were most leery of humans: males are known to raid shambas much more often than females. Such raiding might account for the fact that from the beginning of SCP females seemed more tolerant of humans than males.

Despite these problems, on February 9, 1998 Hunt followed a female to her night nest. He was at the nest site the next day with Esmail Obur, and observed a female leaving her nest. “Unnesting” chimpanzees is a milestone in habituation efforts, and it gave Prof. Hunt a false optimism that full habituation was within sight. February 1998 SCP notched a new record in chimpanzee tracking; the project logged 17 hours of observation. On February 15 Hunt observed a male continuously for over two hours (144 min.).

Jim was replaced by Sacha Cleminson, who averaged three hours of observation a month during his stint between March and October of 1998. With SCP now over a year and a half old, an average of three hours a month over a six-month period, while an improvement over the previous half-year, was still far below expectations. More importantly, it was far below what Hunt had promised in his NSF grant. Cleminson spent even more time in the forest than Latham, our trails were in place; it was clear at this point that habituation would not be easy.

Meanwhile, while Semliki had been safe for some months, the ADF had not disappeared. We occasionally heard news of murders near the reserve, but there was no reason to suspect the reserve itself would become a particular ADF target. We were wrong. During Cleminson’s tenure the ADF committed the most shocking of all the atrocities in its bloody history, and right on the border of the reserve. On June 9, 1998 the ADF came out of the Rwenzoris to attack, of all places, the Kichwamba Technical School, the grounds of which nearly touch southeastern border of the reserve. In the course of the attack they locked more than 40 students in a dormitory and burnt it down. Other students, mostly young girls, were kidnapped and forced to follow the ADF into the Rwenzoris; years later some of the girls were freed. The UPDF pursued the ADF into the hills and reported they had inflicted severe casualties on them, perhaps eliminating them as a military force. Cleminson was unfazed, logging 28 days in the forest the very next month. By now the UPDF had sent a substantial force to western Uganda, just to deal with the ADF. Their presence was reassuring, but at the same time it was somewhat problematic that the government found the most convenient place to billet the troops was in the reserve.

It’s worth pausing to consider the influence of the ADF terrorists on the project and the reserve. It may seem curious, if not suicidal, that Prof. Hunt and his team continued working in the reserve during this dangerous period. There are several reasons it seemed reasonable to continue. First, working in the reserve was not as dangerous as it might seem from the safety of an armchair in some first-world office. There were something like 100 well-armed UPDF troops guarding the reserve, and not only were they ready to meet the ADF in battle long before they got close to project staff, their surveillance was good enough that they often knew where the ADF were, even if they couldn’t defeat them in battle. Second, the attacks in the region were rarely inside the reserve and in fact that the reserve had little in the way of food, cash and alcohol that were the objects of their raids. A third and more important factor for Prof. Hunt was that after nearly every attack Ugandan military authorities and UWA officials assured lodge staff and the SCP that the ADF were were permanently expelled from the reserve if not completely eliminated. These assurances eventually prompted a wry observation from one of our rangers, "for people who don’t exist, the ADF steal a lot of food, drink a lot of booze, rape a lot of women and kill a lot of people."

After two years of slashing, the 50 km-long trail system along Mugiri and it tributaries, as well as a 5km leg along the Wasa, was completed in July of 1998. Prof. Hunt celebrated with the slashing team when he returned to Semliki in August of 1998, for his fourth visit.

By now it had become clear that three factors would make habituating chimpanzees at Semliki extremely difficult. The mosaic of open-canopy forest and grassland in the reserve means the forest floor is quite well lighted, giving chimpanzees very long sight lines, especially when they are in the trees. In most chimpanzee habitats dense foliage allows chimpanzees to be approached stealthily, and individuals often find researchers unexpectedly close. When researchers appear so close, chimpanzees are intelligent enough to realize that if the researchers had meant to harm them, they could have. In this way, chimpanzees at sites with denser foliage gradually learn that humans are harmless. You can’t do that at Semliki. The chimpanzees see humans from a great distance and mostly before the observers see them, and they stealthily withdraw. The dense foliage of most chimpanzee habitats seems to be comforting to chimpanzees; they somehow perceive that it would slow a pursuer, and so they are willing to tolerate observers close at hand. Chimpanzees seem to have a pretty sophisticated understanding of escape routes. An unhabituated chimpanzee sitting in a tree 20 feet above the ground will flee if an observer comes to stand below her; however, in a similar situation if the base of the tree is on the other side of a river or chasm, so that an observer would have to cross the river to reach the base of the tree, a chimpanzee sitting the same 20 feet above an observer will not flee.

A second factor slowing habituation at Semliki is that frequent vocalizations that researchers at other sites rely on to locate chimpanzees are relatively rare at Semliki. Possibly because feeding trees are so dispersed at Semliki, groups are small during daylight hours—though chimps seem to gather in larger groups at night as they begin to make their nests—and small groups vocalize less often. Thus, Semliki chimpanzees cannot be tracked by listening for calls. In combination with a third factor, the constant movement of soldiers, sporadic gunfire and occasional mortar explosions, chimpanzees at Semliki have proven extremely difficult to habituate.

A second factor slowing habituation at Semliki is that frequent vocalizations that researchers at other sites rely on to locate chimpanzees are relatively rare at Semliki. Possibly because feeding trees are so dispersed at Semliki, groups are small during daylight hours—though chimps seem to gather in larger groups at night as they begin to make their nests—and small groups vocalize less often. Thus, Semliki chimpanzees cannot be tracked by listening for calls. In combination with a third factor, the constant movement of soldiers, sporadic gunfire and occasional mortar explosions, chimpanzees at Semliki have proven extremely difficult to habituate.

On March 1, 1999 eight tourists were murdered at Bwindi, in the far south of Uganda. The US issued a travel advisory for western Uganda, and the Peace Corps responded by pulling out their volunteers. To make matters worse, another upstart terrorist group that would eventually merge with the ADF, NALU, declared that westerners would be murder targets.

On March 10, 1999 Hunt returned to assess the situation, his fifth visit. He was also hoping to push forward plans to build a research station so that SCP’s base would be closer to the center of the chimpanzee range. A site was picked out, close to M3.0. The site was—and still is—a beautiful site, and as a bonus there are two tamarind trees on the site, one at each end. On March 16 Hunt followed a chimpanzee to one of the tamarind trees; after feeding he made his nest in a tree that is almost inside what is now the research camp. That same month, March 1999, Hunt received a second NSF grant to develop Semliki and the first scientific publication from the project appeared, an abstract in the American Journal of Physical Anthropology.

British national Esther Bertram served as APD from October 1998 through May 1999. She had been employed at the lodge and liked the reserve so much she offered join SCP. Bertram was followed by James Fuller, who served the May-December 1999 term. He arrived just as reports appeared that ADF rebels had killed four people at Kibale, south of the reserve. Undeterred, Fuller immediately began mapping the trail system (Figure 2), a monumental job. Between mapping and chimpanzee tracking, Fuller spent long hours in the forest. Observations, however, remained stubbornly low, a little over an hour and a half per month.

Hunt made his sixth visit to Semliki from August to October, 1999, during which time he continued pressing UWA to approve plans to build a research station at Mugiri. In retrospect, it seems most likely that multiple revisions to the architectural plans requested by UWA, plans that were always rejected even after the revisions, reflected UWA concerns about the security of the research camp more than concerns about design. Uganda relies on tourist dollars to drive their economy and officials worry that public discussion of security issues might deter tourism.

Despite the assurances of Ugandan authorities, in late November, 1999 it became clear that the ADF had not been destroyed or routed. To Pro. Hunt's horror, they installed themselves directly in the center of the Mugiri chimpanzee community range. Unlike the periodic short-term forays into the research area they had made in the past, they were now hunkered down. Rangers told us the UWA theory was that they were attracted both by the strategic value of the trails and the remoteness and ruggedness of the study site—the UPDF couldn’t get at them with mechanized transport. In response, SCP curtailed activities for a year and a half. During this time there was widespread military action in the chimpanzee range, particularly in early 2000.

On February 4, 2000 the lodge and SCP personnel were evacuated, and as they were leaving ADF attacked three UPDF troops who who had been guarding the Lodge. The three were killed by a rocket propelled grenade. SCP suspended research entirely for a brief time. Lodge staff returned to the reserve several weeks later, and several employees of the lodge volunteered to work part-time on chimpanzee observation, among them Aisling Wilson and Okech Obur, son of Ranger Esmail Obur. For the year and a half from December 1999 through May of 2001, SCP continued with this skeleton-crew staffing, collecting climate data and opportunistic chimpanzee observations. UPDF and the ADF clashed off and on during this time, sometimes with great ferocity. On May 10, 2000 a major battle was initiated near our current research camp, and on May 11 an ADF commander was captured on the research trails, at Obur’s Entrance (see map).Hunt visited in August to assess the situation. It was not encouraging that when in the forest, in addition to the two rangers UWA assigned to the project, the UPDF insisted three soldiers accompany him, one armed with a grenade launcher. He saw chimpanzees for six hours during this month. After sporadic battles for the year between May 2000 and May 2001, on May 12 a major battle was fought on the research trails. It was (incorrectly, as it turned out) reported to SCP on May 15, 2001 that at last the ADF had been truly defeated, chased far from the reserve to the north. The year and a half of military action was a severe setback for SCP. Whereas previous military activity seemed not to affect chimpanzee habituation, the large-scale military operations that began in January certainly did. In February observations dropped to a single minute and remained low well into 2001.

Assured by authorities that the reserve was now safe from the ADF, Prof. Hunt hired Teague O’Mara to carry on research; these assurances turned out to be hollow. Teague arrived in mid-May, 2001, and despite all the recent military activity made a spectacular 9 hours of observation on May 27. Unfortunately, Prof. Hunt’s visit in June and July were a more typical but disappointing six hours a month. On August 20 O’Mara was evacuated in advance of a further battle, the extent of which we were unable to tell. It may have been particularly intense, or it may have occurred particularly near the chimpanzees, but in any case observations dropped from 6 hours in July to 17 minutes in September. Teague returned after this battle, but just as observations picked up in November, another battle was fought. This time the UPDF brought in heavier firepower and repeatedly fired mortars from the rift floor into the chimpanzee range on the escarpment. Now, at last, this truly was the end of the ADF. Since this time although they are reported to persist as a rag-tag remnant pushed into Congo, the ADF have rarely ventured into the reserve. Since 2002 we have been forced to cancel searches only 17 days. Nevertheless, western Uganda’s reputation for violence made recruiting volunteers difficult, and the project suffered an unfortunate run of poor ex-pat assistants. Search-hours were low and naturally hours of observation fell, too.

The effect of military engagement on the chimpanzees is impossible to know. After some of these battles, chimpanzees were not seen for weeks, and they fear-defecated when discovered. After other battles, however, the chimpanzees seemed little different. Still, outright prohibitions of our entering the forest and caution on our part meant our time in the forest was limited, and observations of chimps declined. Assistants were often ordered to enter the forest only with accompanying soldiers.

When the worst of the battles were finally over in November of 2001, the project was 65 months old. There was only one month where SCP had had no presence in the reserve at all, and only six months where SCP searched for chimpanzees fewer than 15 days.

A bright spot for 2002 was the first significant publication on the project, coauthored by the PI, with Bill McGrew (Hunt and McGrew, 2002).

4. Evidence of improving habituation: 2002

As Teague O’Mara’s tenure wound down, a tenure that had seen the worst security problems in the history of the project. While the UPDF and UWA assured SCP the ADF were routed or eliminated, these assurances had not been accurate in the past, so it was not at all obvious that the danger had passed. It seemed to Prof. Hunt that it was time for SCP to suspend operations. Just as he came to this decision, he was approached by a potential volunteer who claimed a military background, and who seemed unfazed by security problems. For whatever reason, perhaps even because the reserve was so quiet, his interest in the project quickly faded. He left after recruiting a couple recommended to us by JGI-Uganda representative Debbie Cox as his replacement.

Despite the recommendation, almost as soon as the couple took over, reports began to filter back to the US that they entered the forest infrequently, entered too late in the day to take advantage of the moring feeding vocalizations, and were not inspiring staff. When their first report reached Prof. Hunt in May, their log showed only 10 minutes of observation for the entire month of April. When Prof. Hunt arrived on May 27, 2002, they had recorded 2 minutes of observation for the month. He fired them.

Despite the recommendation, almost as soon as the couple took over, reports began to filter back to the US that they entered the forest infrequently, entered too late in the day to take advantage of the moring feeding vocalizations, and were not inspiring staff. When their first report reached Prof. Hunt in May, their log showed only 10 minutes of observation for the entire month of April. When Prof. Hunt arrived on May 27, 2002, they had recorded 2 minutes of observation for the month. He fired them.

The project was stabilized by assistant Chris Wade in 2002, even though observations stayed stubbornly low, averaging less than three hours a month. Observations dropped to a shocking low of three minutes in November. Wade had recorded five and a half hours for August, so the decline was puzzling. David Inglis succeeded Wade, serving from December 2002 to June of 2003. Observations improved to five hours a month, and in March, 2003 he logged 9 hours. When Hunt arrived just after the end of Inglis’s tenure on July 4 (with students Shawn Hurst and Randy Patrick) for his tenth visit to the reserve, his first day out he saw chimps for four hours, evidence that habituation was improving. This visit marked the beginning of a slow but rather steady improvement in observation time. Despite periods of inactivity during funding gaps, from this one-year anniversary of the expulsion of the ADF to the present, there has been an uneven but persistent increase in observations.

5. Construction of research camp: 2003

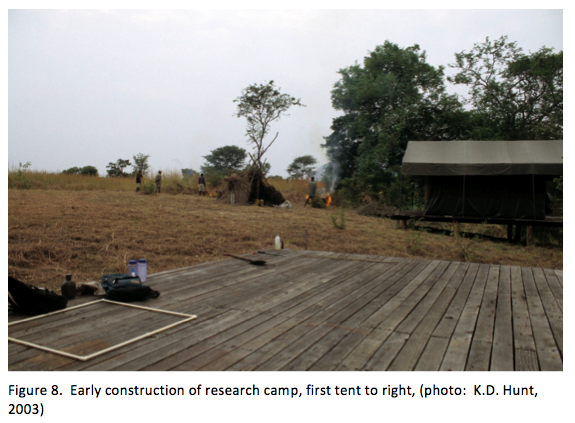

One drag on observation time through 2003 was the necessity for a daily ‘commute’ from the lodge to the Mugiri. It was clear from the beginning that for the project to be successful a camp must be installed near the chimpanzee range. Without a research station or camp staff made one to three trips per day between the lodge and the staging area on the Mugiri. The ‘commute’ was expensive, inconvenient and time-consuming, but even more importantly, it precluded quick forays into the forest, contacts initiated by hearing vocalizations outside of searching times, and other opportunistic observations that might have been expected had the project been sited in or near the chimpanzee range. From the time of the PI’s first grant in 1998 through 2002, three major applications for permission to build a research facility near the chimpanzee range had been submitted to UWA, each complete with its own independently commissioned architectural drawings. After each application revisions were requested and provided. Despite this effort and expense, permission to begin construction had not been granted. At last, during Hunt’s 2003 visit, after eight years in Semliki, plans for a tented camp were approved on July 16.

Unfortunately, by this time most of Prof. Hunt’s grant money had been expended. Hunt made the decision to lay off staff and expend the remaining funds constructing a research camp. Construction was supervised by Clint Schipper and began in October 2003; the camp became habitable early in 2004. There were no attempts at systematic chimpanzee observations for a little over a year, from August 2003 to October 2004, save a visit by Hunt in July, 2004, when he logged 7 ½ hours of observation. During this time he bought, and with Schipper’s help, installed a second large canvas tent on the wooden platforms recently completed by Schipper.

Unfortunately, by this time most of Prof. Hunt’s grant money had been expended. Hunt made the decision to lay off staff and expend the remaining funds constructing a research camp. Construction was supervised by Clint Schipper and began in October 2003; the camp became habitable early in 2004. There were no attempts at systematic chimpanzee observations for a little over a year, from August 2003 to October 2004, save a visit by Hunt in July, 2004, when he logged 7 ½ hours of observation. During this time he bought, and with Schipper’s help, installed a second large canvas tent on the wooden platforms recently completed by Schipper.

During the 2004 visit Prof. Hunt met with a representative of the Heritage Oil Company, which offered a year of support. They funded salaries and provided a vehicle for use by the Assistant Project Director. Many believe that the government's principal motivation in dedication military power to secure stability in western Uganda was the discovery of large oil reserves near Lake Albert. In 1997 the Heritage Oil Company acquired an exclusive oil exploration zone around the reserve. One benefit to SCP was that the Ugandan government and Heritage worked together to improve roads into the reserve. In 1996, when the rehabilitation of the reserve began, the main road from Fort Portal was a precarious and dangerous 20-foot-wide dirt track hugging the mountainside, prone to collapses and landslides. It is now a broad and stable gravel highway, easy to traverse, and much safer.

6. Proximity to research group dramatically improves observation: 2004-2006

Jim Reside became the first APD to live in camp full-time, beginning in November, 2004. During his tenure he built a kitchen/dining room structure (Figure 9), erected a third tent, installed a water collection system, installed solar panels, built a toilet, and put in a shower. His work brought the camp infrastructure up to full functionality. His great energy also brought observations up, if slowly, throughout 2005. He averaged nearly 10 hours of observation a month, the second best six-month average ever, double the observations of the previous six months, which had been double the six months before that.

Jim Reside became the first APD to live in camp full-time, beginning in November, 2004. During his tenure he built a kitchen/dining room structure (Figure 9), erected a third tent, installed a water collection system, installed solar panels, built a toilet, and put in a shower. His work brought the camp infrastructure up to full functionality. His great energy also brought observations up, if slowly, throughout 2005. He averaged nearly 10 hours of observation a month, the second best six-month average ever, double the observations of the previous six months, which had been double the six months before that.

In May and June 2005 Prof. Hunt visited, installed a fourth tent, bought beds—real beds with frames and mattresses—bedding, mosquito nets, tables and other furnishings to bring SCP Research Camp up to something close to its current condition.

Assistant Carmen Vidal arrived in June, 2005 and quickly began to log more hours in the forest than anyone previous or since. She achieved project maxima for two of our four most telling objective measures of habituation: she averaged 25 hours of observation per month over her six-month tenure (including 40 hours in July, 2005), and she searched on average a staggering 30 days a month. She observed chimpanzees an average of 22 days a month, and she discovered chimpanzees 65% of her attempts. Vidal's time in the forest was impressive, but it meant that donor relations were not as robust as they might have been. Perhaps it would have happened anyway, but shortly after she arrived, Heritage withdrew funding. Eventually Indiana University stepped in to provide a bridging grant.

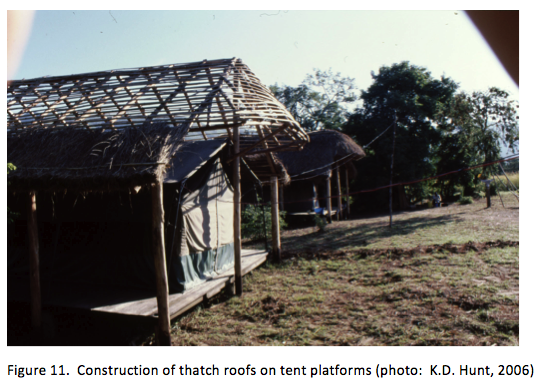

Assistants Jess Tombs’ (Feb.-July 2006) and Alissa Jordan’s (July-Dec 2006) observation hours were only slightly below Vidal’s; they averaged 17.2 and 21.3 hours of observation per month during their respective stints. Tombs oversaw the construction of thatch canopies over the tents, necessary because of both the intense sun and the lashing rain that can occur during the wet season. In the midst of Tombs’ stint, in June of 2006, Prof. Hunt accompanied the first outside ape research specialists to make an extended visit to the site, Linda Marchant, Bill McGrew and Jim Moore. Hunt sought their advice on speeding up habituation, research design and securing funding. Two of Hunt’s doctoral students, Gil Ramos and David Samson, visited Semliki to lay the groundwork for possible doctoral projects, and another student, Randy Patrick, made a second visit. Jordan not only extended observations, but put some finishing touches on the dining structure that were much appreciated by staff.

Assistants Jess Tombs’ (Feb.-July 2006) and Alissa Jordan’s (July-Dec 2006) observation hours were only slightly below Vidal’s; they averaged 17.2 and 21.3 hours of observation per month during their respective stints. Tombs oversaw the construction of thatch canopies over the tents, necessary because of both the intense sun and the lashing rain that can occur during the wet season. In the midst of Tombs’ stint, in June of 2006, Prof. Hunt accompanied the first outside ape research specialists to make an extended visit to the site, Linda Marchant, Bill McGrew and Jim Moore. Hunt sought their advice on speeding up habituation, research design and securing funding. Two of Hunt’s doctoral students, Gil Ramos and David Samson, visited Semliki to lay the groundwork for possible doctoral projects, and another student, Randy Patrick, made a second visit. Jordan not only extended observations, but put some finishing touches on the dining structure that were much appreciated by staff.

7. Funding hiatus suspends research: 2007

When Jordan’s tenure ended in December, 2006 grant funds were exhausted. Research was suspended. On the strength of Vidal’s and Tomb’s improvement, Prof. Hunt submitted a National Science Foundation (US) grant in August 2006, but the grant was not funded, nor were several smaller proposals. Referees consistently pointed to poor progress on habituation as the principal reason for rejection, and certainly this criticism was justified. The lack of funds necessitated SCP running a skeleton crew for a year and a half, from Christmas Eve 2006 to May 23, 2008 when Indiana University stepped in with a $30,000 two-year research grant.

8. Surge of volunteers: 2008-2009

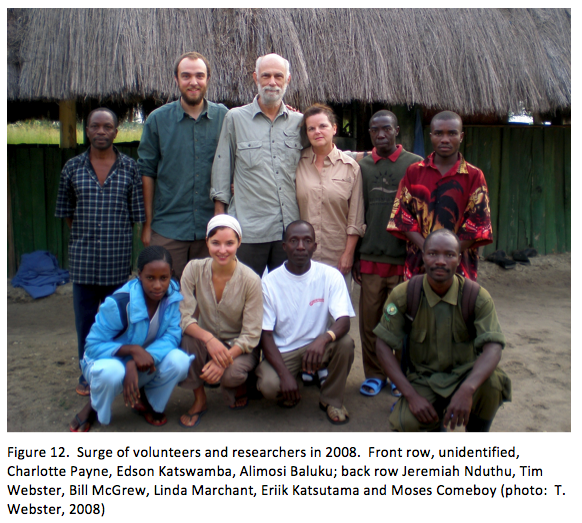

In 2008 SCP was joined by two distinguished chimpanzee researchers, both with wide experience habituating chimpanzees, Linda Marchant and Bill McGrew. From May to November of 2008, with the aid of Profs. Marchant and McGrew, SCP recruited six volunteers to aid with habituation. Hours of observation and search times hit record highs. In August, 2008 SCP staff observed chimpanzees over 70 hours, three hours per contact. Even so, it remained clear that habituation was not complete. For comparison, at Gombe in 1986 Prof. Hunt had averaged 10 hours of observation per contact. Nor was SCP staff able to follow chimpanzees for long distances on the ground; the chimps were still just too skittish.

One discouraging discovery during 2008 was made by APD Tim Webster. He visited the Muzizi forest to check on the status of the community there, a group that had not been observed by outsiders since a visit by Prof. Hunt in 1998. Webster reported that the Muzizi had been decimated, presumably for charcoal production. This destruction was particularly heart-breaking, because UWA soon began building a tourist site in nearby Ntoroko. Had Muzizi become a tourist site, the chimpanzees there might have survived. Prof. Hunt strongly recommended to UWA that patrols be initiated in the Muzizi, the forest allowed to regenerate, and chimpanzees allowed to repopulate this important area, but to date no action has been taken.

One discouraging discovery during 2008 was made by APD Tim Webster. He visited the Muzizi forest to check on the status of the community there, a group that had not been observed by outsiders since a visit by Prof. Hunt in 1998. Webster reported that the Muzizi had been decimated, presumably for charcoal production. This destruction was particularly heart-breaking, because UWA soon began building a tourist site in nearby Ntoroko. Had Muzizi become a tourist site, the chimpanzees there might have survived. Prof. Hunt strongly recommended to UWA that patrols be initiated in the Muzizi, the forest allowed to regenerate, and chimpanzees allowed to repopulate this important area, but to date no action has been taken.

Following the large influx of volunteers in 2008, early 2009 was relatively quiet. Unfortunately, the first six months of 2009 saw observations drop to a disappointing low not seen for years, 8 hours per month, only a quarter of the observations in the six month period previous. In the first three months of 2009 the longest observation was only 2 hours. For this six month period, chimpanzees were sighted only 9 days per month, and hours of observation were a mere quarter what they had been during the previous six months. The decline was probably due to low search-hours by the APD. Later observation showed that habituation had not deteriorated: when Prof. Hunt arrived in July 2009 he identified four new chimpanzees in the first few days and logged a 9 hour follow.

One of the milestones of habituating chimpanzees to human observation is the ‘nest-to-nest follow.’ A chimpanzee that allows a human to follow him or her for an unbroken 12-13 hours must have a high toleration for humans, so a 'nest-to-nest' is a very good thing. It also has a further consequence: when individuals break off contact with an observer, it can be days before a group is re-discovered. In this case, trackers must systematically cover the trail grid hoping to stumble upon an individual, or they must locate a feeding party when they vocalize. Re-discovery can be difficult. Once individuals can be followed throughout the day up to nesting, researchers can arrive at the nest before dawn the next day to extend observations another day. With this increased proximity to humans, habituation can improve quickly, and the unbroken chain of observations builds on itself. SCP awaits this the nest-to-nest follow anxiously.

Maggie Hirschauer took over as Assistant Project Director on July 1, 2009. On July 13 Hunt and Hirschauer worked in tandem to follow a feeding party for 10 hours, losing them at 5:47, only two hours before nesting. Under Hirschauer, hours of observation rose to levels near those in 2008, when we had 3 and 4 researchers searching each day.

9. 2010: Mugiri community has 29 males

Hunt visited briefly in January of 2010, and on January 26, he and incoming APD Caroline Deimel observed two males in a tamarind tree for an hour, unusual because tamarinds are found in open areas, where Semliki chimps have been very skittish in the past. Two new males were identified in January to bring the total to 23. On March 28, Deimel came within a hairs-breadth of the nest-to-nest follow, logging 11 hours and following an individual from 7:15 to 6:05. By the end of Deimel’s tenure, it had been established that there were 29 males in the Mugiri community, 26 that we could identify, and three further males that are still indistinguishable to us (see Chimp IDs). During Deimel’s tenure, hours of observation rose to 18 ½ per month.

Hunt visited briefly in January of 2010, and on January 26, he and incoming APD Caroline Deimel observed two males in a tamarind tree for an hour, unusual because tamarinds are found in open areas, where Semliki chimps have been very skittish in the past. Two new males were identified in January to bring the total to 23. On March 28, Deimel came within a hairs-breadth of the nest-to-nest follow, logging 11 hours and following an individual from 7:15 to 6:05. By the end of Deimel’s tenure, it had been established that there were 29 males in the Mugiri community, 26 that we could identify, and three further males that are still indistinguishable to us (see Chimp IDs). During Deimel’s tenure, hours of observation rose to 18 ½ per month.

In June David Samson took over as APD in August of 2010, assisted by his fiance Holly Green. They raised observations still further, to average 22 hours of observation a month.

SCP has enough inertia that several setbacks during and immediately after Samson’s tenure have only slowed us slightly. On October 31, 2010, one of our slashers, Moses Comeboy, was severely injured when charged by a buffalo. Moses healed slowly, and required physical therapy in Kampala. He is on the mend now, and was promoted to camp manager. Soon thereafter staff were barely able to prevent a brush fire set by poachers from burning down camp. Our stalwart Toyota Surf Runner endured many scrapes, but in early January 2011new assistant Barbara Kubenova rolled in near the Wasa bridge and it has gone to the big junkyard in the sky. Will Symes took over as APD on short notice soon after, arriving in April, 2011, and endured his entire tenure without a project vehicle. Despite this handicap, in July, 2011SCP hosted six volunteers in camp, including Joel Bray, Abby Kearny, Hector Manthorpe, Alicia Rich, and Austin Senteney, in addition to APD Will. Observations were strong for the remainder of Symes term

Late in 2011and the first half of 2012 unexpected staff turnover, partly due to ex-pat health problems, came at the same time that ivory prices skyrocketed. Parks in Africa that had not seen elephant poaching for years suffered increased pressure, and sadly Semliki has not been immune. Late 2011 and early 2012 we encountered more snares, more poaching camps, and more burning than in years past. Our chimpanzee observations suffered along with the elephants. From May to July, 2012 APD Jeremy Borniger stepped up our hours in the forest, but there was no increase in chimpanzee observations. Increased monitoring during SCP Director Kevin Hunt's six week stay in June and July seems to have dealt with the snare problems, but Kevin Rolnick, who took over as APD in July, 2012 found two poached elephant carcasses on the chimp trails in a two month period. Kevin was replaced in January 2013 by Corey Mitchell, and thankfully as she begins her term our staff are not reporting snares on the trails, and elephant poaching seems to have abated somewhat, at least at Semliki.

Kevin D. Hunt, January, 2013